Artificial intelligence is transforming how we design and build. By 2050, the effects of AI adoption will be widely felt across all aspects of our daily lives. As the world faces a number of urgent and complex challenges, from the climate crisis to housing, AI has the potential to make the difference between a dystopian future and a livable one. By looking ahead, we’re taking stock of what’s happening, and in turn, imagining how AI can shape our lives for the better.

.jpg?1586819389)

Artificial intelligence is broadly defined as the theory and development of computer systems to perform tasks that normally require human intelligence. The term is often applied to a machine or system’s ability to reason, discover meaning, generalize, or learn from past experience. Today, AI already utilizes algorithms to suggest what we should see, read, and listen to, and these systems have extended to everyday tasks like suggested travel routes, autonomous flying, optimized farming, and warehousing and logistic supply chains. Even if we are not aware of it, we are already feeling the effects of AI adoption.

As Alex Hern explored at The Guardian, making predictions on the next 30 years is a mug’s game. However, the act of following trend-lines to possible conclusions and imagining how we might live is a productive exercise. We’re taking a closer look at how artificial intelligence will shape design by 2050. From air taxis and urban intelligence to construction and the Singularity, AI will continue to shape how we live, work and play.

The Future of Work

According to The Economist, 47% of the work done by humans will have been replaced by robots by 2037, even those traditionally associated with university education. These jobs will be lost as “artificial intelligence, robotics, nanotechnology and other socio-economic factors replace the need for human employees.” Editorial Data & Content Manager Nicolás Valencia explored this idea two years ago and how automation will affect architects. The conclusion is that the most difficult jobs to replace require a high level of creativity and human interaction, and have a low percentage of repetitive activities. These will be the last to be replaced, but there will also be new jobs created that will become necessary to monitor and coordinate intelligent machines and systems.

As we approach a time when the broad intelligence of AI exceeds human levels, existential questions arise. What should you study when any job can be programmed or replaced? Will universal income be adopted as a result? Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates believes so. “AI is just the latest in technologies that allow us to produce a lot more goods and services with less labor,” says Gates. How we work, and what we can work on, will begin to change at an increasingly faster rate. If half of all work can be done by robots or machines in the next 15 years, it’s likely that all work will be shaped by AI before 2050.

Urban Intelligence & Big Data

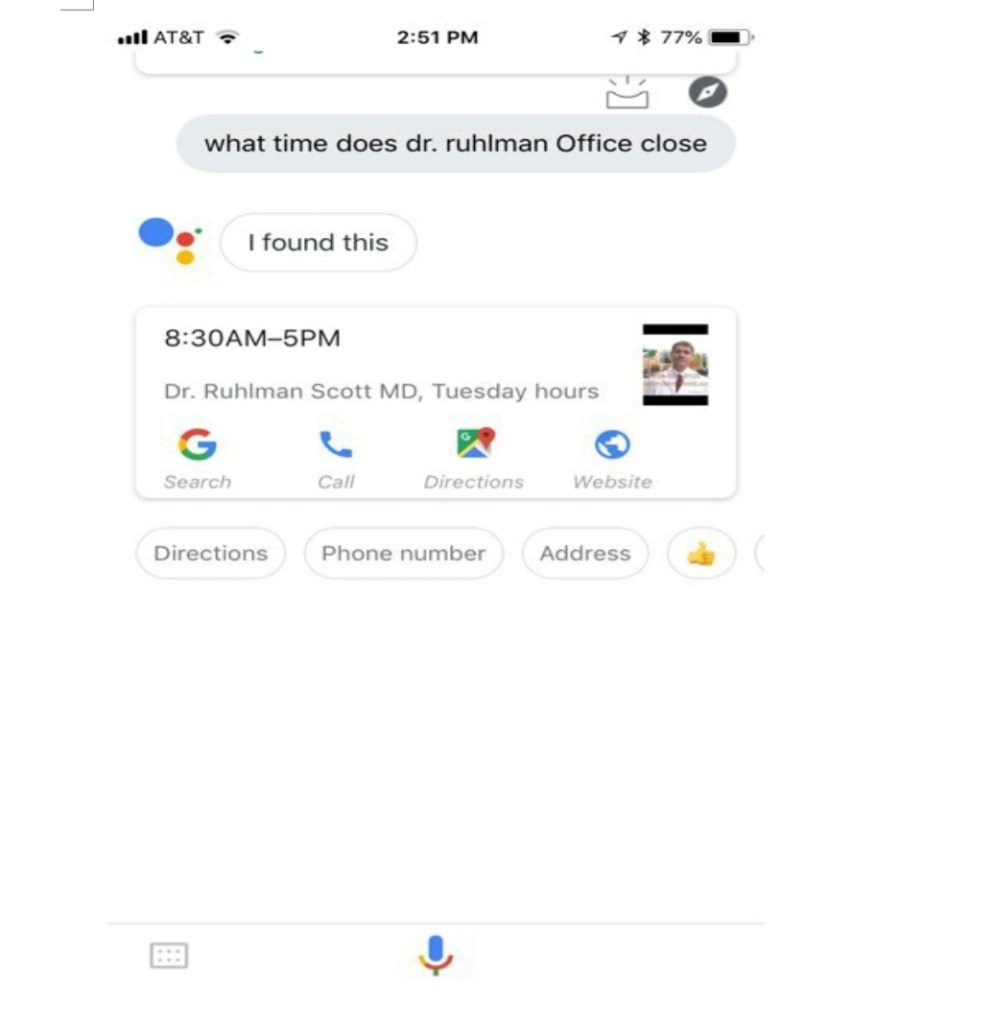

AI and the “Internet of Things” are changing how we live, and in turn, society at large. Architect Bettina Zerza has explored how data and intelligent systems will dramatically shape our cities. She gives the example of micro sensors and urban technology that will record air quality, noise pollution and soundscapes, as well as urban infrastructure at large. How people move, where emissions are worst, and how efficient city processes are represent just a few of these ideas.

Today, 55% of the world’s population lives in urban areas, a number that will increase to 70% by 2050. Projections show that urbanization could add another 2.5 billion people to urban areas by 2050, with close to 90% of this increase taking place in Asia and Africa. Here, AI can further analyze and monitor how we move about the city, work together, and unwind. In 30 years, we will also have entirely new versions of these modalities.

Artificial intelligence will continue to inspire discussions on the precarity of work, our shared ethics, ideas like universal basic income and urban intelligence, as well as how we design. More than productivity gains, we can rethink the way we live and how we shape the built environment. By doing so, we can being to imagine new creative and social processes, and hopefully, work with AI to lay the foundation for a better future.